Books Are Back... Maybe?

A possible return to books in the book industry may just lead to… well… people buying books.

A few developments in the publishing industry recently seem to point to a promising trend: publishing and book selling is realizing that what they’re about is, well, books.

I want to highlight two stories here that seem to indicate this trend, or at least made me hopeful. It starts with Barnes & Noble opening sixty stores this year. Sixty! In an age when apparently it’s all about digital and online shopping. Then Simon & Schuster have announced that they will no longer require blurbs (endorsements) for books. How these two relate will be clear as we go along.

Barnes and Noble’s Crazy Return

We’re having a bookstore revival. Or so says Fast Company. Yes, even while A.I. threatens it all. Yes, even when apparently “less people read than ever before” and no one buys books (which I’ve heard consistently ever since I actually even learned to read). Yes, even when apparently we keep hearing about how the future is digital and everyone wants to do everything online (hint: they actually don’t!).

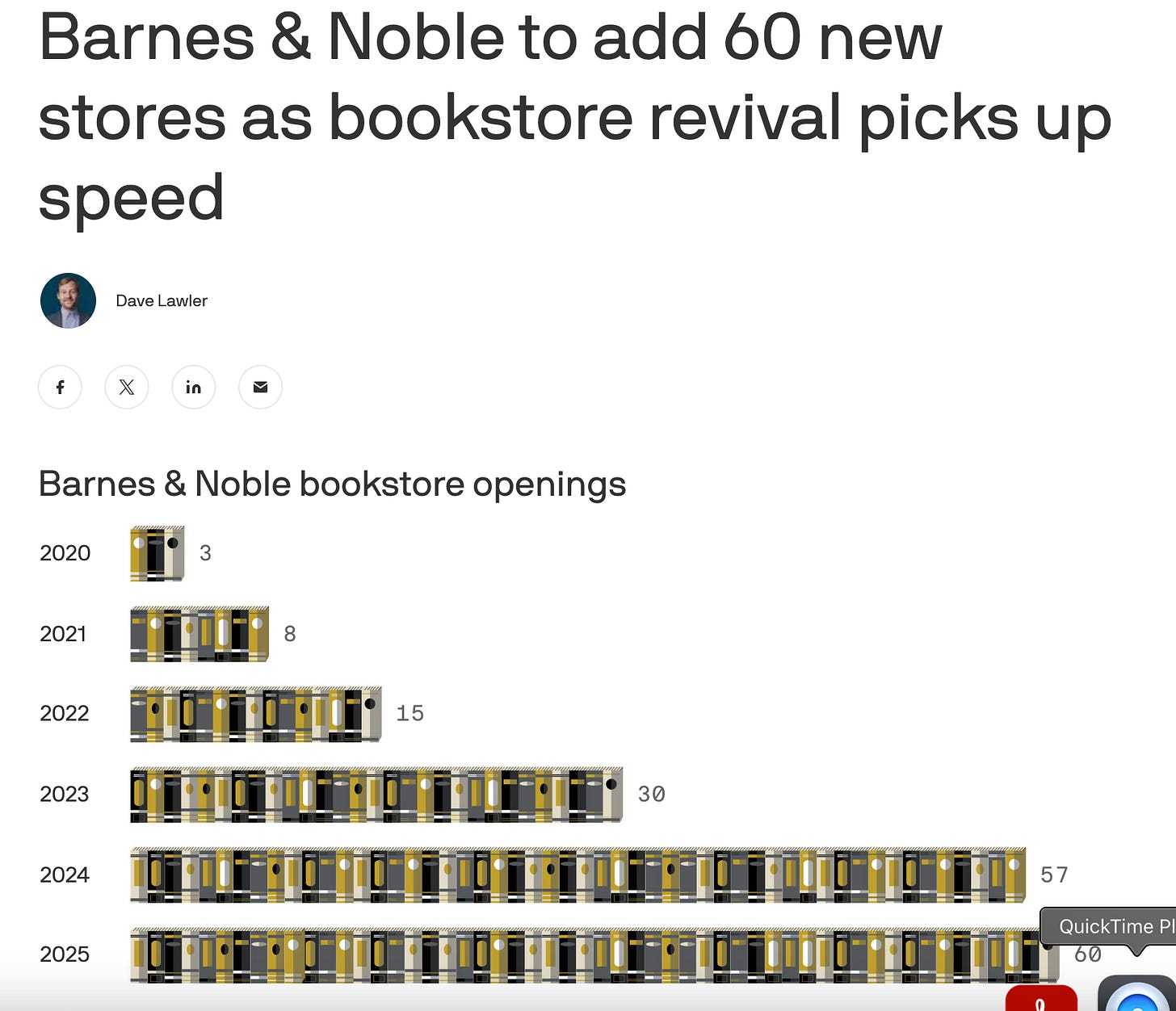

Here’s a nice diagram from Axios to illustrate Barnes & Noble’s surprising turn around since 2020.

“In 2024, Barnes & Noble opened more new bookstores in a single year than it had in the whole decade from 2009 to 2019,” says Fast Company.

Why?

“[The company] is enjoying a period of tremendous growth as the strategy to hand control of each bookstore to its local booksellers has proven so successful.”

The positive trajectory was so quick, so clear, that in 2022 one of Barnes & Nobles’ biggest competitors, Amazon, completely pulled out of the bookstore race. One would think if anyone had all they needed to make it work it was Amazon. But it seems you need something more.

Something obvious.

So what happened?

The answer starts with James Daunt—a man who turned around the British book chain Waterstones, and then in 2019 was hired as the Barnes & Noble CEO. Straight away, as you can see from the diagram above, things started turning around. One would expect the opposite from the pandemic years.

How? The answer lies in what seems so obvious and yet so difficult for so many people to really understand. James Daunt loves books.

“As with any good bookseller, I am obsessed with the book as a physical object,” he told Publishers Weekly. “We intend to make our stores places that enhance the beauty of physical books. Give me a Sarah J. Maas [American fantasy author] book that has a nice new cover and we will light it up.”

And he loves the bookstore. So much so that he downsized corporate and gave power to the stores to make decisions on what books they would sell and how they would display and organize their store. As he told The Guardian in 2023:

“Amazon doesn’t care about books… a book is just another thing in a warehouse. Whereas bookstores are places of discovery. They’re just really nice spaces.”

Each store is allowed to tailor for the context and community it finds itself in. It can lean into the power of personal, local curation. This has made a massive difference. One of the ways in which he did this was by ending lucrative “co-op” deals with publishers. These deals meant that publishers would pay for prime space in stores nationwide, and (for a yearly fee) decide what of their catalogue would be displayed in important spaces, like the entrance of the store. This however made every Barnes & Noble a copy of the next.

The problem is readers who really love books and who are the obvious core client base for a bookstore don’t like too much conformity. They like surprises. They like aesthetics. They like to find hidden gems. And when you cater to these readers, you get everyone else too.

The co-op agreements were actually also big money wasters. As per the Guardian:

Though Barnes & Noble was making revenue from these deals, Daunt argues it was ultimately losing more. With the co-op agreements, which he has now ended, the chain was returning 30% of its inventory unsold – about $1bn worth of books. Now, that’s down to 7%. “When you’re running your bookstore properly, it’s about 3%,” he says.

These things seem almost surprisingly obvious, but the fact is they weren’t to a lot of people. Prior to Daunt’s appointment, Barnes & Noble was trying everything to stay afloat. Instead of selling books, it increasingly sold toys, curios, and board games. It even opened up full service cafés called “Barnes & Noble Kitchen”. It seemed they were selling everything else except books. And those “Kitchens” did not do well at all (not surprised).

Now it’s making a big deal out of books and catering to bookish people and it’s working. Who would have guessed?

Then something else happened recently which hints that perhaps, at last, the publishers are catching on too.

Publishers may get back to publishing and selling… books?

Last year September, Simon & Schuster appointed Sean Manning as the new Publisher for its flagship imprint. Manning is an interesting character who seems to understand, well, books. By January, Manning already ‘shocked’ the industry by stating the obvious about blurbs (book endorsements), indicating that Simon & Schuster would no longer require authors to get these anymore for the flagship imprint. As he stated in Publishers Weekly:

“I believe the insistence on blurbs has become incredibly damaging to what should be our industry’s ultimate goal: producing books of the highest possible quality. [emphasis mine.]

“It takes a lot of time to produce great books, and trying to get blurbs is not a good use of anyone’s time. Instead, authors who are soliciting them could be writing their next book; agents could be trying to find new books; editors could be improving books through revisions; and the solicited authors could be reading books they actually want to read that will benefit their work—rather than reading books they feel they have to read as a courtesy to their editor, their agent, a writer friend or a former student. What’s worse, this kind of favor trading creates an incestuous and unmeritocratic literary ecosystem that often rewards connections over talent.

“I don’t want my favorite writers writing blurbs—I want them writing more books so I can read them!”

Does not all this seem rather… obvious? What else would you want writers to do except to, well, write? What else do you want your editors doing except, well, edit?

What do you want readers to be doing except, well, reading?

I think this all points to a well-needed trend that I hope ramps up. In my opinion there are a few things the publishers have done in recent times—and that writers have also been complicit in—that has led to so much difficulty for the industry.

1. Publishers insisted on giving already-platformed celebrities book deals

This seemed like a good idea at the time. Just pair celebrities with ghostwriters, and the book is done. Marketing is a cinch. Ride the wave that’s already there. Everyone wins.

Except writers don’t, of course. The ghostwriters win (I’ve been a ghostwriter for many years, so I don’t have a problem with that, generally) but what about writers who want to build a writing career writing their own books? As in, being a writer? They were not winning. So a lot went independent.

I think there were some winners under this give-a-book-deal-to-someone-with-an-already-existing-big-platform model, but also big losses—and more losses to come. One example: $20 million to Prince Harry and Meghan Markle for a book deal that has now dissipated. As per MSN: “[Vanity Fair reported] how these two, their work ethic is incredibly questionable, their collaboration skills are not so strong, is that potentially why Penguin Random House no longer [has a deal with them]."

(Of course, the new book deal was for a divorce book, which means they would need to get divorced to do it! It seems they’re not, but I don’t keep up with celebrities much!)

I wonder how much money they lost that Harry and Meghan just walked away with.

Celebrities engage in a popularity contest, and you could pay a popular celebrity big money today only to see it fizzle to nothing tomorrow when some scandal hits social media. A lot of these celebrities also do struggle with what is required from authoring a book, even if a ghostwriter is doing the writing: the ability to collaborate; and the ability to focus on only one thing for weeks or even months on end. You can only do so much of these kinds of deals, but to build a whole industry around it… that’s a bad idea, and it’s coming home to roost.

Especially as social media becomes less influential going forward. It should become increasingly obvious that big social media numbers don’t really mean nearly as much as they used to. They simply don’t translate to sales.

In fact, there is no real data supporting that a large social media following results in better sales. Tim Grahl at Book Launch shows that, in fact, it may not translate to book sales at all, or very little. It’s not that having social media accounts isn’t helpful, but more that it functions as a space for people to find out more about you, to be able to engage with you, and for you to take advantage of publicity when it does come.

For example, indie author Devon Erikson recently seems to have made a fair number of sales when he was banned from an indie science fiction competition which he apparently didn’t even enter. (The story went like this—the competition, or someone else, nominated him; the competition suddenly drew up ‘rules of conduct, and found him guilty of breaching them; then the competition banned him and publicly ousted him for breaching rules of conduct for a competition he never even knew he entered.) This little fiasco resulted in so many people (including me) finding him on social media, discovering where to buy his book, and buying it.

People who can build big social media platforms may not be equipped to well… write. Because spending time building a social media platform is time they should be spending writing.

If only Manning would extend his statements above to social media. Who knows? Maybe he will.

2. Publishers didn’t think long-term

The bigger problem with the sign-the-celebrity or person-with-already-a-big-platform approach is about longevity. Here’s what celebrities or people with big platforms do: they look for the best deal. You’re not signing up partners, you’re signing up people who are going to drop you as soon as something better comes around. Maybe you’ll get one big book out of them, and it may be lucrative, but it’ll be short-lived.

The good publishers in the past invested in helping develop a writer’s career, because they knew a good relationship with a writer meant more books written down the line—and good ones. If you invested in a writer, developing them, there were good odds they would probably stick with you and add value to your business. One hit wonders are great, but longevity is what keeps businesses lasting for the long haul.

Investing into one-hit wonders is never a good model for the long game.

3. Writers didn’t stick and also played the game

I think there were definitely occasions when writers played the game and used publishers to build their platform, and then they ditched at the next best opportunity. They were not looking for partners but for stepping stones.

These statements are not going to win me any friends, but think about it. If you were a publisher and, as soon as an author hit success, they ditched you—and this happened multiple times—what would you do? Continue to invest in writers? No, you’d look for some sure bets. You’d look for people with already-established platforms.

We don’t often hear about this from the publishers’ side because they tend to keep their weaknesses away from the public limelight, but I suspect this was in many ways what happened in the last few decades. It was something of a two-way street.

Of course, many writers had to do this of necessity, especially as the publishing industry shrank as the big corporates kept buying everyone else, resulting in only the “Big Five” publishers we have today, and leaving many authors “orphaned” as editors opted out of looking after them, or editors lost their jobs, etc. Thankfully, right now, a blossoming indie publishing scene is giving the Big Five a serious run for their money—which is why I think people like Manning have been brought on board to put things into a different direction at Simon & Schuster.

For my part, I am positive a turn-around for publishing only requires a few basic facts to be acknowledged:

a. People still love books.

b. Writers still love to write.

c. Publishers just need to love publishing.

d. Bookstores just need to love being bookstores.

I believe that’s all it takes.