Holy Week Viewing: The Mission

A wonderful work of art that reminds us how the Institutions of State and Religion always clash with what is good, true, and beautiful.

Being Holy Week, I felt in the mood to watch some sort of Christian-themed movie. After a couple of King Arthur false starts (it turns out most “King Arthur” movies are not actually very good), I settled on The Mission—a film that I certainly consider, after watching, to fall well into the kind of art film category that doesn’t go over your head (or is just a lot of aesthetic posturing) but yet encourages you to think deeply.

The Mission (1986) was one of our film studies in school. At the time, I didn’t understand it or care for it, and I couldn’t remember much from it at all before watching it now. But I was glad I watched it now because not only is its message so relevant for Holy Week but it’s also so appropriate for our current politically-charged climate.

Directed by Roland Joffé and starring Robert De Niro, Jeremy Irons (and Liam Neeson), The Mission was nominated for seven Academy Awards in 1987 (it won “Best Cinematography”) but received mixed critical reviews. If you’re looking for a movie to watch for Holy Week, I recommend it. Here’s why.

The perpetual clash of true believers with institutions

(Spoilers incoming!)

The movie follows Jesuit priest Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons) as he establishes a Christian mission with the Guaraní people deep in the South American jungle, and Rodrigo Mendoza (Robert de Niro), a mercenary and slave trader who comes to faith after killing his own brother. But when Spanish colonial powers decide to cede the mission’s land to the Portuguese who want the Guarani as slaves, these two take opposite approaches. Gabriel opts to respond with nonviolence while Mendoza chooses to fight.

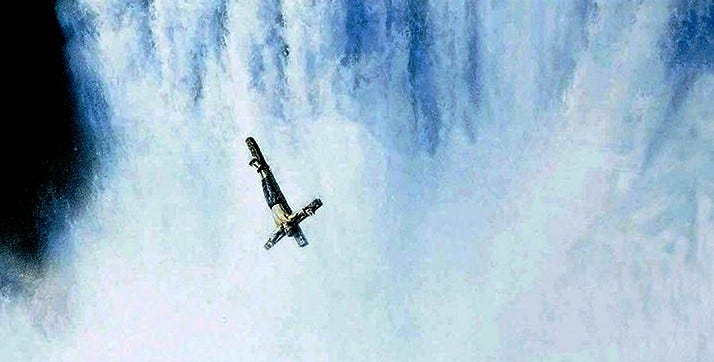

Both lead to the same outcome: complete and tragic loss. The Guarani are almost wiped out as the Portuguese come to claim them, and their missionaries who loved them so dearly are gunned down—one while fighting, the other while walking, headstrong and firm, with a cross in his hands.

Mendoza is the first to be killed. As he lies dying, he sees his friend Gabriel—who is responsible for the new life he found at the mission—marching forward with his converts, holding his cross firmly, standing for his ideals of God’s love to all. You can see the anticipation on Mendoza’s face: will Gabriel’s approach work when his own has failed? The answer comes swiftly: Gabriel is mercilessly shot again and again. Mendoza lays his head down realizing that both have failed. The point is clear: neither the sword nor love could save the Guarani in the face of State power and economic gain.

At that point you feel the injustice of it all and you wonder why God would not bother defending either of these men who stood for what was right. But the lines that come next from the other key characters solidify the point of the movie. Papal emissary Cardinal Altamirano, who had to decide which of the missions could remain under Church protection (but was directed by both Church and State to see that none could; and he did not fight them or seek to convince them otherwise) asks the Portuguese, in tears, if all the bloodshed was necessary, especially in light of the fact that he gave the final go-ahead for them to march in.

“The world is thus,” is the answer he receives.

“No,” he replies. “Thus we have made the world.”

The next line is the clincher:

“So your holiness,” writes the Cardinal to the Pope, “Now your priests are dead and I am left alive. But in truth it is I who am dead and they who live.”

You realize: despite being so savagely gunned down, the priests get the better deal, for they are now finally free from the unjust, despicable world that functions in such a manner. But the man who tried to play the Court (the Cardinal) and was forced to make a decision for the sake of State and Religion was the man who must live with his own cowardice and compromise for the rest of his life. He ultimately got the bad deal.

And thus the conclusion: those who follow Jesus and His ways are always, always, going to be at loggerheads with the powers of State and Religion. These two institutional powers always clash with what is good, true, and beautiful. The ways of Jesus are simply incompatible with institutional power and its agendas. You can’t merge the ways of Jesus and these powers together. The best you can do is try and negotiate your way through their spiderwebs and hope to get out the other side without too many scratches (good luck!) but when you join them you will be forced to compromise, every time. The Institution always only has one goal: preservation of the Institution. The good guys always end up dying at the feet of the agendas of State and Religion. There are always ‘economic’ considerations before human ones. But perhaps the good guys who get killed get the better deal: final freedom from the institutions that so mercilessly rule our world.

Holy Week

It’s the same story during this week leading up to Jesus’ death and resurrection—Holy Week.

On Palm Sunday, Jesus is praised by the crowds as they anticipate Him to be the one who will free them from the Roman State that so unjustly rules over them. However, throughout the week, Jesus does nothing but irritate everyone. He overturns the tables in the Temple, rebuking the religious powers. He hangs out with the poor and needy, showing that He is not interested in political power. Jesus is never interested in getting connected to the right people who can make things happen. In fact, he refuses to acknowledge their power and influence as necessary or even slightly important when it comes to the Kingdom of God. By the end of the week, the State and Religious powers, fed up with it all, have conspired together to kill him, and they stir up the crowds that praised Jesus just a week before to ask the State (in its graceful mercy [sarcasm]) to release to them Barabbas, a revolutionary leader who at least understood the program and what needed to be done. This Jesus, however, who seems to get nothing done and won’t play the game—let him be crucified.

And so at the hands of the State and Religion, Jesus goes to the cross, and the people are both helpless and complicit. No one comes to his defense. Those that seem to want to are scared and confused. As my friend Charlie Harrisberger said to me this week, there is one thing we are always assured of: when Religion is ruffled, someone is going to die. Jesus was ruffling Religion his entire ministry. He snubbed the ruling institutions not by revolution but by largely treating them as irrelevant to God’s real plans. Everyone knows someone is going to die when you do this, so they stay clear of the authorities and let Jesus be the scapegoat.

The book of Revelation and the Mission

The final book of the Bible reiterates the point through picture language. Here we have Beasts, false prophets and anti-Christs—usually interpreted as State power (Beasts) and Religion (false prophets, anti-Christ) oppressing the world. These enemies are animated by spiritual powers (dragon) that work in the background. We realize that these Institutions tend to take on a life of their own and yet humanity seems to happily and too often give power to them for the sake of security (idolatry in the Old Testament is the same set up).

In fact, the whole Bible is full of this message. From Genesis when the city-states were being set up by priest-kings who encouraged idolatry and first merged State and Religion together, consolidating their power; to Revelation; we see the narrative is that State and Religion are always the Chimera who function against God’s ways in the world. In contrast to his contemporaries, Abraham is a sojourner—ultimately the “father of the faith” is the man who lived away from institutional demands and seemed to have his eye on Another Country. So it is with all who truly want to follow Jesus. The Mission of God throughout the Scriptures is always after something different than State and Religious power, a fact that the movie The Mission portrays so well.

Our current climate

This speaks so marvelously into our current context where the State today has once again shown itself, throughout most of the world, to be what it always was: corrupt and empty. But right now we live in a world where the State, exposed, is showing its Beastly tendencies. This is happening practically everywhere.

At the same time, in some quarters, Religion is seeking to hop on for the ride again. Or perhaps the reigning Religion for the last few decades—a secular humanism—is coming to an end, and there are other and eager religious powers waiting to fill in the vacuum.

I’ll leave it at that.

The Mission portrays this reality through a poignant telling of historical moment. It’s a slow burner by contemporary standards. You’ve got to pay attention. But that’s what makes for good art. Joffé’s work perhaps never lived up to this film afterward, but it’s one that still deserves attention almost forty years later.