When Rejects Make Culture

A lesson from the Impressionists in how scenes form, and the importance of community in changing culture.

Normandy, France. Spring, 1874. The rejects of the Salon de Paris, the much-admired, loved and adored official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts—widely touted as one of the greatest annual or biennial art events in the Western world (until 1890)—are exhibiting their work on the second floor of a photography studio. They call themselves the “Cooperative and Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”. Amongst them are Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Claude Monet. They cheekily name their exhibition the “Salons des Refusés” (Salon of the Rejected).

Art to be exhibited at the Salon de Paris was determined by a group of artists, academics and critics known as “The Jury”. They were the ones who decided what was Good, what was Great, what was Worthy to be called Art. And they had resolved that these kids, with their rough, “unfinished” style, were not painting anything Worthy. On those rare cases where they did agree to showcase these kids’ work at the Salon, they placed it so high in the exhibition halls that no one could even see them. They were just not interested in what these kids had to offer.

The kids, for their part, had now had enough of this. If no one would showcase their work, then they would do it themselves.

They would go indie.

Making an “impression”

One of the works being displayed by Claude Monet at their scorned-by-the-establishment “Salon of the Rejected” exhibition is called Impression, Sunrise. A journalist by the name of Louis Leroy has come to their exhibition and would later write sarcastically of this painting:

“Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it... and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

So… he didn’t like it.

That painting was sold to art collector Ernest Hoschedé for 800 francs. Hoschedé actually had a lot of faith in these artists, especially Monet. Four years later, that painting was sold at an auction for 210 francs. So people really didn’t see much worth in it.

Today, that painting is worth $250 to $350 million, making it one of the most valuable paintings in the world. It was initially not Worthy, and now look how much it’s worth!

What happened? How did it change?

The rise of a scene

The Salon; the “Jury”; the Establishment were going about business as usual. But as Establishments go, they became gatekeepers rather than supporters of innovation. And so they missed what was going on in the ‘underground’—what the younger generation were gradually getting interested in.

There is a history to why the impressionists were doing what they were doing. Back in Paris in 1862, Eugène Delacroix is an old soul with a lot of artistic experience. He is influenced by the classic works of Michelangelo; of da Vinci; and of Rembrandt (a rebel in his time!). He is widely traveled, incorporating influences from Greek and Roman culture, as well as North African culture. He is influenced by illustrated works from the likes of Shakespeare. And at the moment he is drawn to the brushwork of Peter Paul Rubens—who creates this feeling of motion in his work—expressive and full of color.

Three young men are sitting on a wall in a courtyard to spy on this old soul. They are Frédéric Bazille, Auguste Renoir, and Claude Monet. Two of these are part of this rebellious exhibition mentioned above. The third, Bazille, is going to die in the Franco-Prussian War, and will never experience the respect people will have for his art much later.

Delacroix is experimenting with paint in a way that has these kids in awe. They would spy on him and learn, taking the techniques—the wild brushstrokes; the use of color—and later head to the village of Barbizon, where artists were painting the landscapes and pieces exhibiting life in the French country, with loose brushwork and a certain softness. The “Barbizon school” would later become known as the art movement that inspired the Impressionist movement, but it starts with Delacroix who, for those young men, bridged the gap between the old and the new that made their new so enduring.

A place for a scene

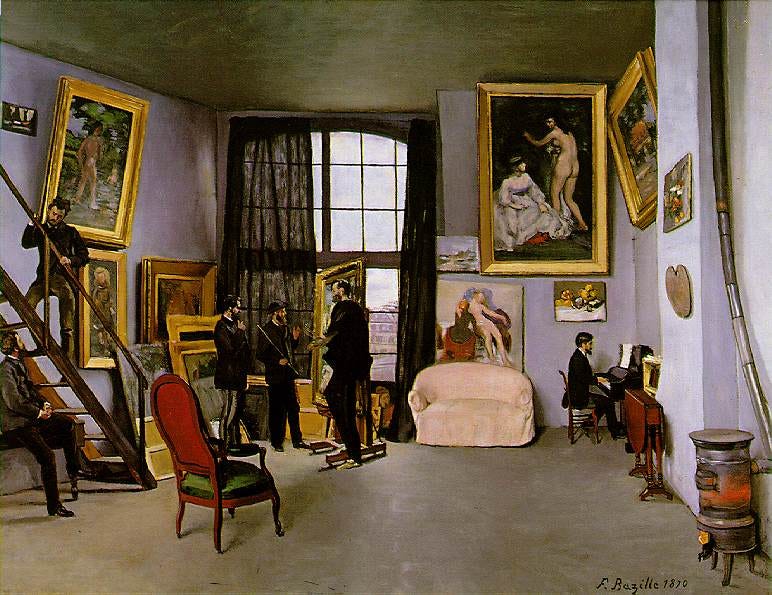

Realizing they needed a space of their own to work, Bazille and Renoir would return to Paris after Barbizon and rent a room in the Batignolles neighborhood at 9 rue de la Condamine. Bazille captures what was going on in that studio so poignantly for us in his piece Studio: 9 rue de la Condamine.

It’s like a glimpse into something secret. We get to almost see inside the embryonic stages of an art scene that would be the first of its kind.

, in his book Rembrandt is in the Wind (which I highly recommend—link below) tells us about it:“His Studio; 9 rue de la Condamine gives us a peek into this era of art history in Paris. In this painting, we see Bazille showing one of his new paintings to [Édouard] Manet and Monet. Renoir sits to the left, talking with the French novelist and playwright [also journalist] Émile Zola. At the piano sits one of their musician friends, Edmond Maître. Three of Bazille’s known works hang on the wall… and what appears to be a Monet, possibly one Bazille had purchased.”

Musicians, journalists, painters, novelists, all hanging out. Ramsey encourages us now to “stop and consider what was happening in this little studio.”

“No less than seven of the world’s most celebrated painters gathered to work on their craft, but even more, to be part of this community of artists. They shared a common perspective on where they believed art was going, which Bazille summarized by saying, ‘The big classical compositions are finished; an ordinary view of daily life would be much more interesting.’ These artists were testing new waters, trying new techniques, hoping to introduce something new into an area of culture known for resisting and even scoffing at attempts to defy convention.’”

Then Ramsey so wonderfully points out the point I’d like to drive home:

“It’s imperative for these artists to work in community, not isolation. They needed one another. They needed to be around each other. They needed to be able to share a common space—a place where they could gather and speak freely.”

Bazille, who would later pass away due to war, was so key in setting all this up for this group of artists that at the time no one knew but were to become superstars over a decade later. Rejected by the Establishment but believing in each other, they later set up their own exhibition. Monet doesn’t really know what to call his work, so he plays into the term that depicts the hazy nature of the painting and that had come to be used by the critics, the Press, the Jury, the Establishment to disparage the Barbizon art scene—Impression.

And what is rising is a new art movement. It’s just that no one outside of the movement realizes it yet, they’re too busy gatekeeping.

The timeline of failure… and success

The original exhibition of the Impressionists, while exciting, drew a lot of criticism—as highlighted by Louis Leroy’s sharp comments above.

In the following year, 1875, the Impressionists decided to hold an auction of their works. The day before, however, a newspaper critic took a shot at them, writing that they painted like a "monkey with a box of paints". Protestors came to scoff and jeer, to the point that the police had to be called.

In 1876, still determined, they held another exhibition. A reviewer calls them all “lunatics” and daubers”. But there is a positive review in the New York Tribune. The Americans seem more open to this new style. While they didn’t sell much in the exhibition, Monet does sell one of his paintings for 2,000 francs, which is a breakthrough.

In 1877, their next exhibition is held at the apparently more impressive premises on rue Le Peletier (apparently where the Paris Opera used to be until 1873). A review in the Arts Chronicle says: “Children entertaining themselves with paper and paints do better.”

Two years later, they hold another exhibition, and 15,000 people show up. By now, their image of being rebels is helping to sell the movement. People tend to like a good rebel. The negative Press have actually helped this cause. Americans are also now catching the wave, and one of them (Mary Cassatt) exhibits as well.

Between 1887 to 1926, the Impressionist movement is in full swing.

Community in real space is where a scene happens

This story highlights for me so many important components of what it means to make art—and make art that can inspire movement and change. The Impressionists were rebels. They wanted to redefine the traditional ideas of art and painting and capture the fleeting moments of life, the ‘impressions’ of the world they experienced. They did this through the use of unmixed colors, spontaneous brush strokes, and painting outdoors (“en plein air”). Impressionism is widely believed to be the first true Modern art movement, influencing other art forms too, like music. Composer Claude Debussy was highly influenced by the Impressionist style and took the mindset to music. It inspired him and others to make use of advanced harmonies (9th and 11ths) and apply modal techniques (originally devised by monks in the Middle Ages) in a different way. Those wild brushstrokes, those stand-out colors, and Debussy (and other) influences led to a music style called jazz. You might have heard of it.

It’s an example of how a scene starts underground and rises to prominence. It starts with a simple thought: our work is actually good. What if we do it without the Establishment? What if we go indie? It inspires a new generation that years later incorporate it into other areas of culture no one really would have guessed.

And the emphasis there is on the we. A cultural movement does not happen at home on the internet, just you and your paint brush, being your ‘true self’ with no one to critique or tell you anything. It happens in community with people working together, bouncing ideas off of each other, dreaming with each other, investing in each other, truly loving each others’ work, critiquing each other and cheering each other on. Much like a church—or what a church should be (not a megachurch which encourages individualism and surface-level community based on consumer taste and basically choosing your desired spiritual life off a menu).

I think it’s important for artists who truly want to make a difference in culture today to reject the Spotify approach to art and life—an individually-focused, algorithmically curated playlist that matches you to what you already like. It keeps you boxed into your own individual Establishment, as it were. You don’t have to listen to anyone else’s opinion. You don’t really need to expand your horizons, or even be irritated with someone else’s tastes or ideas. You can live in your own private world. You don’t need to go anywhere, meet anyone, or do pretty much anything. Just keep scrolling. You can stay Safe, and stay dead.

Or to reject the megachurch approach—we’ll take a shallow approach to life and spirituality and paint a veneer we’ll call “community” over it—having a form of community but denying its power.

OR, of course, we can escape our boxes and make art together again. That’s what creates a scene. I vote for the latter!

Inspirations

Enjoy this slide show (put it on 0.25 speed and stream it to your TV) of Impressionist paintings.

Special thanks to

for his book, Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art through the Eyes of Faith that inspired this post, specifically chapter 6. (Also thanks to my in-laws for buying it for me! :) ).